Our new report, Unfinished Business, examines the issue of methane leaks from Canada’s non-producing wells. The report’s author, Amanda Bryant, Senior Analyst at the Pembina Institute, answers questions about the environmental risks associated with these leaks and how this problem of proper well clean-up should be addressed in a way that is fair to Canadian taxpayers.

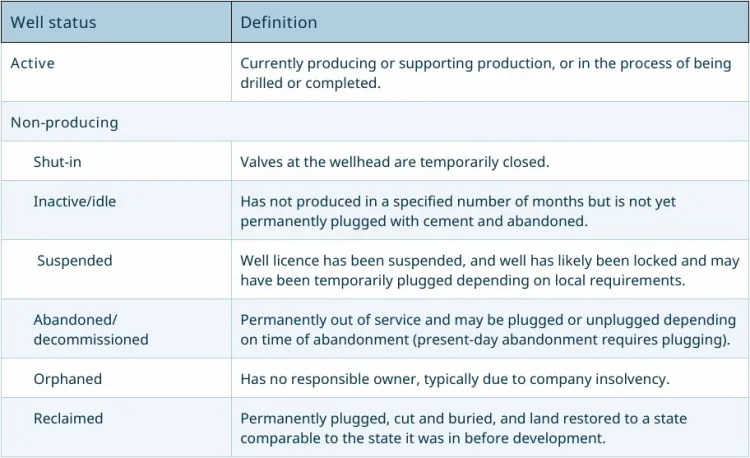

Question: What is a non-producing well, anyway? There are so many different terms that get thrown around: “shut in”, “idle”, “inactive”, “suspended”, “abandoned”, “decommissioned”, “orphaned”. How do you make sense of it all?

What unites all these terms is that they refer to oil and gas wells that are not currently in use (i.e. not currently producing or supporting the production of oil or natural gas, nor in the process of being drilled or completed).

Beyond that blanket definition, the specific terminology can be very confusing. It doesn’t help that jurisdictions define these terms in different, sometimes contradictory ways. However, the table below captures the uses of the terms we’ve noted in Canada’s major producing regions (Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia).

It’s important to note that, in all cases, oil and gas companies that drill wells have a legal obligation to remediate the land once they’ve finished production. The issue — as the definitions below show — is that there are many different ‘states’ a well can be in between the point where it stops being used to regularly produce oil or natural gas, and the point where it can be fully classified as reclaimed. Because there are no mandatory closure timelines, companies often leave wells in limbo, neither producing nor fully abandoned and reclaimed, where they can leak methane and other pollutants for years or even decades. Because there are no mandatory closure timelines, there is nothing preventing companies from leaving wells in limbo — neither in use, nor fully abandoned and reclaimed — where they can leak methane and other pollutants for years or even decades.

Q: How big of a problem are methane leaks from these wells?

The short answer is: a pretty big deal, and bigger than we previously thought.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that has over 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in a 20-year timeframe. This makes tackling methane emissions one of the most powerful levers we have to reduce the near-term impacts of climate change.

One overarching problem with methane emissions from the oil and gas sector is that, in general, they are under-estimated, so it’s hard to know the true scale of the problem. With active infrastructure (i.e. oil and gas wells and other sites where production is still happening), measurement studies have shown that emissions are 1.5 times higher than official estimates.

The most up-to-date estimate says that non-producing wells were responsible for about 11% of Canada’s oil and gas sector methane emissions in 2023 (6,440 kt CO2e). That’s about the same carbon footprint as Canada’s whole railway sector (5,937 kt CO2e). This means that these wells are a significant source of methane leaks — far more significant than has been previously recognized.

In addition, there is a real spectrum in terms of how often and how much unused wells are leaking — plus lots of variation across regions. For example, wells that have been properly plugged typically do not leak much, but not all plugged wells are properly plugged according to modern standards. Wells can sit idle for decades before being plugged, and even plugged wells can have problems, such as poor quality cement that leads to leaks later.

Some wells appear to be at greater risk of leaking, like horizontally drilled wells and shallow gas wells. But risk factors can vary across regions, too, so studies are needed to identify the characteristics of wells that make them more prone to leakage in each region.

This is another reason why draft amendments to Canada’s oil and gas methane regulations, which would introduce monitoring requirements at non-producing wells, should be immediately finalized. Addressing leaks from non-producing wells is just one more area where governments and regulators can show real leadership on methane — an area of policy which requires continuously raising the bar and challenging ourselves to do better as we learn more about the scale of the problem.

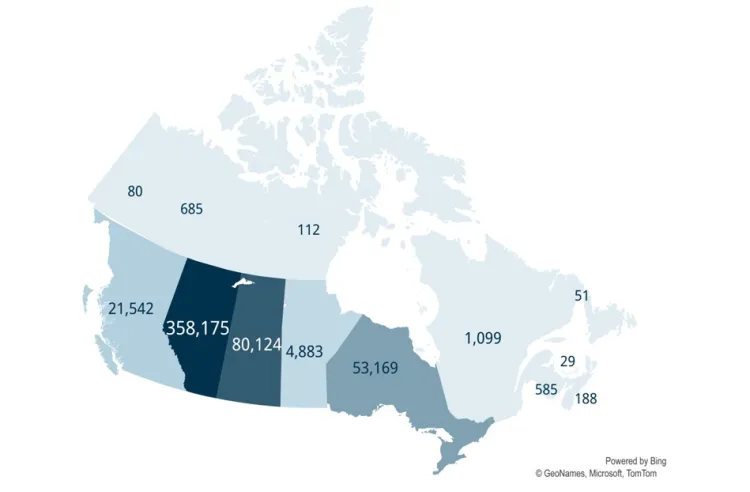

Figure 1: There are estimated to be over 500,000 non-producing wells across Canada.

Q: Aside from methane’s contribution to climate change, are there other environmental risks associated with these leaking wells?

Yes. Methane does not only leak into the atmosphere; it can also contaminate the fresh water that sits underground in aquifers (known as groundwater), which is often used for agricultural and industrial purposes. One recent study found that 94% of groundwater that is used in the United States comes from aquifers that also have orphan wells situated within them — meaning that there is significant risk of contamination.

It’s also worth noting that, while you might tend to picture oil and gas wells in sparsely populated or rural areas, this isn’t always the case. Many can be found in population centres, including near residences. In these contexts especially, methane emissions can pose a risk to human health. For example, methane emissions are also sometimes accompanied by hazardous co-pollutants like benzene (which is known to cause cancer) and sour gas (which can be fatal, but can also cause loss of consciousness and respiratory distress at lower concentrations). For a decade, the Norfolk County community in Ontario has been exposed to sour gas emissions tens of thousands of times higher than what’s legally allowed. Community members have been dealing with nauseating smells, headaches, burning eyes and sore throats.

Finally, the methane emissions that come from non-producing wells can make them an explosion risk in built-up areas. A historic well was recently discovered near several homes in Bonnyville, Alberta, and the homes had to be vacated and demolished so the well could be decommissioned and any risk of explosion removed. Abandoned wells in urban areas of Ontario have also led to explosions.

Q: This sounds like a mess — a harmful and potentially dangerous mess. Shouldn’t someone be made to clean it up?

Absolutely. There is a common-sense principle known as the Polluter Pays Principle that captures this idea. It’s a simple thought: those that cause pollution should be responsible for the cost of cleaning it up. It’s about basic responsibility and fairness. And it isn’t controversial; polling of Albertans showed that 94% agree that the financial burden of well clean-up should fall mainly on oil and gas companies.

The Polluter Pays Principle is enshrined in Canadian law through the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, which is the federal law through which many emissions regulations, including the proposed oil and gas methane regulations, are delivered. Provincial legislation like the Alberta Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act is also meant to uphold this principle. This reflects the fact that, while such regulations are largely about reducing emissions from high-polluting industries, they also exist to ensure Canadians don’t unfairly shoulder the costs that those emissions create — be it the financial costs of extreme weather events caused by climate change, or the costs of cleaning up pollutants and unused infrastructure. This is something all governments should consider when they assess the utility and value of emissions regulations — especially as they are sometimes misrepresented as irritants that cost companies money and impede economic growth.

All proposed government policies relating to the management and closure of mature oil and gas infrastructure should be evaluated for how well they uphold the Polluter Pays principle. For instance, we’re not convinced that all the ideas contemplated in the Government of Alberta’s proposed Mature Asset Strategy pass this test. In fact, we think some of them — like creating Crown corporations that shift responsibility for mature assets from oil and gas companies onto the Crown — introduce significant risks of taxpayers ultimately ending up on the hook for clean-up costs.

As the energy transition unfolds globally, more oil and gas companies are likely to reach insolvency, and the problem of non-producing wells is therefore likely to grow. This makes this issue — of ensuring companies, not Canadians, pay to clean up — even more urgent. And, since oil and gas reclamation work needs to be carried out by skilled labourers, this — like other aspects of methane mitigation — could be an important area for new jobs that are adjacent to the oil and gas sector.

Q: So what are the top few policy changes that are needed to better address methane emissions from non-producing wells?

We make lots of policy recommendations in our new report, so if you want some specific, actionable ideas, definitely look there. But in general, there are 4 main things governments need to do:

- Disincentivize long-term inactivity using tools like regulated closure timelines and strengthened quotas. In other words: prevent as many wells as possible from ending up in the ‘limbo’ state where they’re potentially leaking methane over years or decades.

- Improve data by standardizing data collection, prioritizing quality checks, and supporting measurement and monitoring initiatives, so that we can get a better handle on where, when, why, and how much wells are leaking.

- Understand regional context and tailor policies to it by ensuring leaks and their causes are studied in each region and provincial closure rules reflect those studies.

- Address risk by prioritizing monitoring at wells that might be at greater risk of leaking, like horizontally drilled wells, shallow gas wells, wells abandoned prior to the implementation of testing requirements and modern plugging standards, and wells that may have been plugged with substandard materials.