Earlier this month, the Government of Alberta released a new report about its emissions reduction progress. The report was based on data from Canada’s National Inventory Report, the latest version of which was released earlier this year, and covers up to the end of 2023. This is the same data that the federal government uses to report back on Canada’s progress on our international climate change commitments.

Alberta’s report contained some big claims – most notably, that oil and gas production has increased while emissions from the sector have fallen. These are important points, especially at a time when the province is apparently seeking a so-called “grand bargain” with the federal government as it begins to zero-in on a list of nation-building infrastructure projects, including a potential new oil pipeline to carry bitumen to the West Coast. Precise details are unclear, but it appears this “grand bargain” would entail the federal government fast-tracking the environmental approvals for a new privately-funded oil pipeline (if one were proposed – currently there is no proponent), if the oilsands industry follows through on its longstanding pledge to dramatically reduce its upstream emissions, likely via the Pathways Alliance carbon capture and storage project, first proposed four years ago. Prime Minister Carney said any oil that would go into any future pipeline would need to be “decarbonized.”

In this context, being clear on Alberta’s emissions performance – and, by extension, the emissions performance of the oil and gas industry – is very important.

Claim 1: Alberta’s overall emissions have declined by 9% since 2015

While this statement is correct, it is important to put it into context.

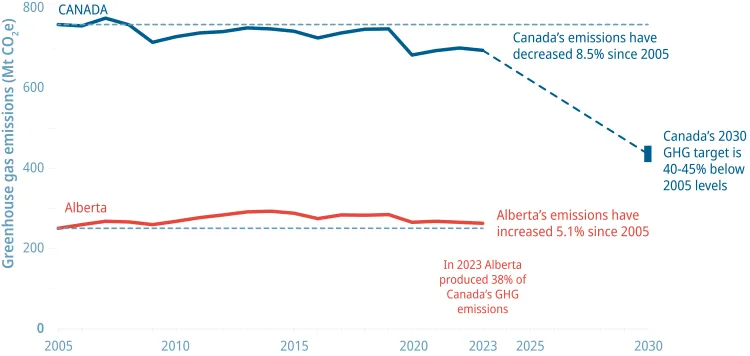

Since 2005, the international baseline against which our climate progress is measured, Alberta’s emissions have increased by 5%. This compares with an 8.5% reduction across all of Canada since 2005. Alberta is therefore not yet aligned with Canada’s progress overall. (Canada’s national target by 2030 is a 40–45% reduction from 2005 levels.)

Claim 2: Alberta had the greatest absolute reduction in emissions of any Canadian province or territory between 2022 and 2023

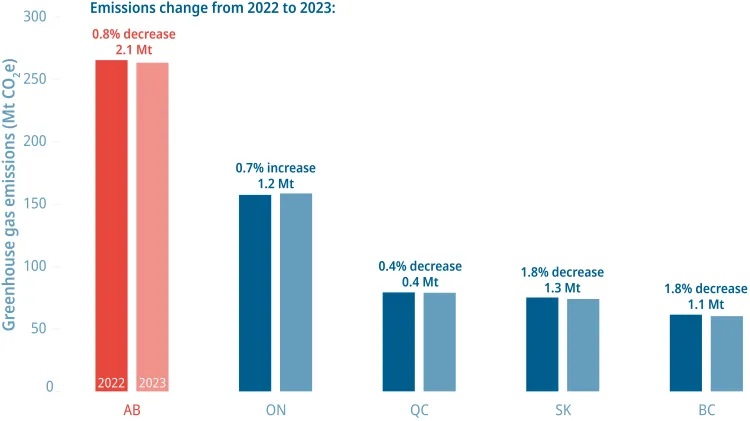

Alberta emitted 263.4 megatonnes (Mt) of greenhouse gases in 2023, which represented a reduction of approximately 2 Mt from the previous year (265.5 Mt). This is indeed the largest amount of Mt that any province reduced emissions by that year.

However, because Alberta’s emissions are so high (in 2023 the province was responsible for 38% of Canada’s overall emissions – a similar proportion as in 2022), we would expect it to reduce the highest number of Mt each and every year, in order for it to make a fair contribution to Canada’s efforts on climate change. This is why, globally, climate targets are per cent-based targets, rather than absolute reduction numbers – because it would be unfair to expect smaller countries with much lower emissions to reduce the same number of Mt every year as larger countries with much higher overall emissions. The same principle works in Canada: every province should be aiming to reduce emissions on a trajectory to a 40–45% reduction by 2030, and net-zero by 2050.

Alberta’s 2 Mt reduction represents a decrease of 0.8% year-on-year. Some other provinces therefore actually reduced their emissions by more than Alberta did, relative to their total – as the graph below shows.

Claim 3: Oilsands emissions continue to decline

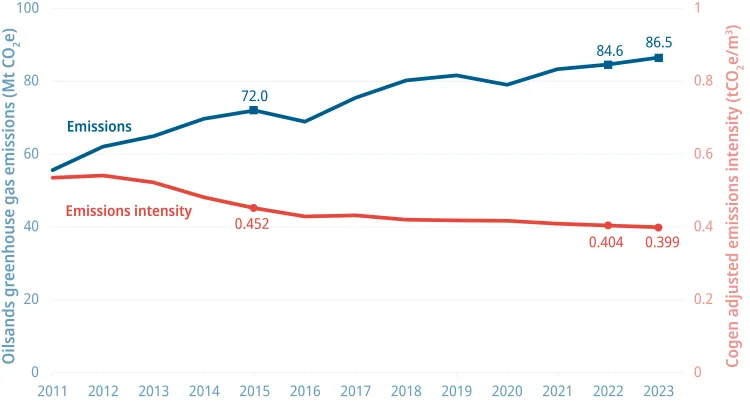

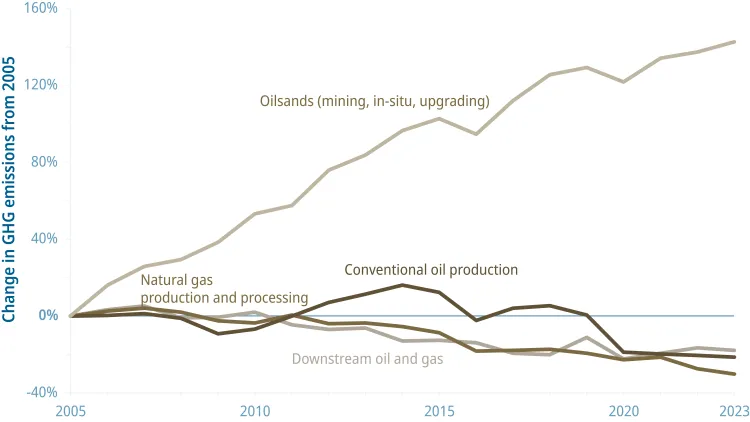

Absolute emissions from oilsands production have gone up every year except 2020, due to lower production during COVID. Oilsands emissions were 86.5 Mt in 2023, up from 84.6 Mt in 2022, and have increased 142% since 2005.

It’s possible this claim was actually meant to be about emissions intensity (the amount of emissions per barrel of oil produced). That did see a marginal improvement in 2023 (from 0.404 tonnes CO2e/m3 to 0.399 tonnes CO2e/m3, or about 1.2% improvement). But it’s worth noting, as the above graph illustrates, that progress on emissions intensity has otherwise been largely stagnant for the last five years. In any case, these gains are being offset by production growth, meaning overall, emissions from the oilsands are still growing.

Emissions figures on the oilsands are particularly important for the so-called “grand bargain” that the premier of Alberta is seeking to strike with the federal government over a new pipeline, which Premier Smith has said could carry as much as a million barrels of oil per day. Even if the quid-pro-quo was this theoretical pipeline would be fast-tracked in return for the oilsands companies finally following through on their Pathways Alliance project, the level of increased production that would be needed in the oilsands to fill it would likely wipe out the emissions gains their project would achieve.

Indeed, even if the Pathways project went ahead on schedule and was capturing 10–12 Mt per year by 2030 (as the companies originally stated was possible), this would still only represent about 15% of the current annual oilsands emissions (89 Mt). If a new pipeline and new production happened at the same time, the Pathways project could have an even smaller impact on oilsands emissions.

Claim 4: Emissions associated with conventional oil and natural gas production are falling.

More precisely, the government press release pointed to the following numbers:

- Conventional oil emissions have declined 19% since 2015, while production increased by 7%.

- Natural gas production and processing emissions have declined 24% since 2015.

As we’ve shown in our analysis in the past, it is the case that all subsectors of the oil and gas sector (the two listed above, plus the downstream – as shown in the graph below) have indeed achieved emissions reductions since 2005.

But due to the big rise in oilsands emissions in that same period, on average, overall emissions for Alberta’s whole oil and gas sector are still going up – by 29% since 2005. In addition, given that the oilsands accounts for more than three-quarters of oil production in Alberta, singling out the emissions from conventional (non-oilsands) production doesn’t tell the whole story. The fact is, oil production in the province – when adding together conventional and oilsands – is still very emissions intensive.

Claim 5: Alberta’s emissions reductions have been achieved without federal policies

More specifically, the government press release had a quote from Minister of Environment and Protected Areas Rebecca Schulz that said “we don’t need top-down policies from the federal government to do this.”

The first thing to note is that our analysis of the data suggests Alberta – either on a whole-economy basis, or just looking at the oil and gas sector – is not yet achieving emissions reductions on a scale that would be necessary to play a meaningful role in Canada’s climate commitments. The province is still by far the biggest contributor to the country’s overall emissions, with oil and gas production still Canada’s biggest source of emissions (around one third of Canada’s overall emissions still come from that one sector – around 13% alone comes from the handful of companies operating in Alberta’s oilsands).

However, where the province has made gains – most notably in its electricity sector (where it correctly stated emissions have declined by 45% since 2015) and in oil and gas subsectors other than the oilsands (as shown above) – it is highly likely that federal policies, or the equivalent regulations Alberta has implemented to align with those policies, have played a significant role.

The gains made in the electricity sector, for example, are largely a result of the federal coal regulations, which saw the last coal-fired electricity plant in Alberta cease operations last year. Meanwhile, Alberta’s methane regulations, which the federal government deemed equivalent to its own, have likely been the key driver behind the gains made by conventional oil and gas producers in the last several years, where those regulations limit venting and flaring at oil and gas production sites, and have improved methane leak detection regimes.

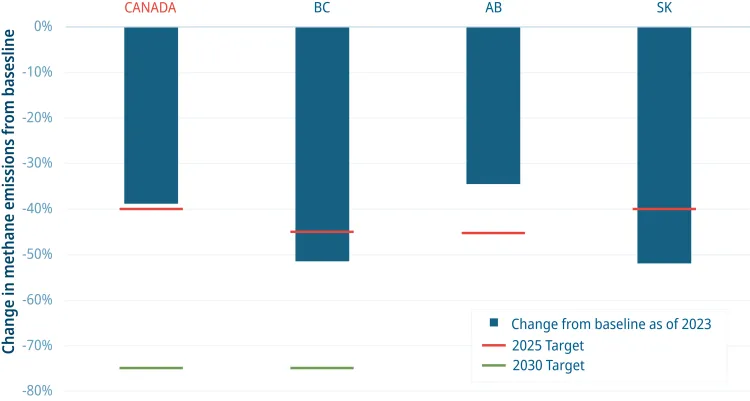

Claim 6: And, while we’re talking about methane…

Alberta says its methane emissions have declined 45% since 2015, but as our latest research shows, based on the National Inventory Report (which uses more accurate emissions models and data), Alberta’s oil and gas methane emissions actually declined by about 35% from 2014-2023. That means the province has not yet met its 2025 target – unlike British Columbia, which met its 2025 methane target two years early, while growing natural gas production.