Last week’s memorandum of understanding between the federal government and the Government of Alberta was a step backwards for reducing methane emissions in Canada. While much of the focus has been on a new bitumen pipeline as a project in the national interest, the federal government gave ground on the Clean Electricity Regulations, oil tanker ban, and proposed emissions cap. What some people don’t realize is that one of the items of agreement that might sound like a win was really a backslide that will result in more emissions and opens the door to further delays.

Alberta’s commitment to a 75% reduction in oil and gas methane emissions by 2035 is a significant concession from Ottawa. Canada has a commitment to reduce oil and gas methane emissions 75% by 2030 (from 2012 levels). It can’t achieve this target unless all provinces where oil and gas is produced – especially Alberta – pull their weight.

Urgently reducing oil and gas methane emissions is the biggest no-brainer we have when it comes to decarbonization. Fixing leaks, swapping out venting equipment, and capturing emissions conserves gas that would otherwise be wasted. Implementing these solutions often results in companies actually saving money over time, because when you capture methane, you capture valuable natural gas that can be used or sold. It’s so practical that over 50 international oil and gas companies have voluntarily pledged to basically completely eliminate methane emissions by 2030.

Federal regulations to achieve that 2030 target were drafted 2 years ago and have been on the cusp of finalization for months. Alberta would have been required either to implement the regulations as written, or design provincial regulations to achieve equivalent outcomes – something B.C. has already done. In effect, Alberta would have been beholden to that same 75% by 2030 target as the rest of the country.

Instead, the federal government has hamstrung its own regulations on the much-awaited eve of their publication by saying “it can wait” to the province where action matters most.

The costs of delay

You might be saying: but 75% is 75%, isn’t it? What does it matter if it’s achieved now or later?

It matters a lot.

Think of it this way. Imagine you smoke 10 cigarettes a day. You decide to cut back from 10 to 2. You could start tomorrow. But suppose you decide to start five years from now, instead. Terrible choice! Every day between now and then, you’ll smoke 8 more cigarettes than you would have if you had cut back right away. Those cigarettes will add up fast (amounting to 14,600 extra cigarettes over five years!). You and your lungs will suffer the consequences.

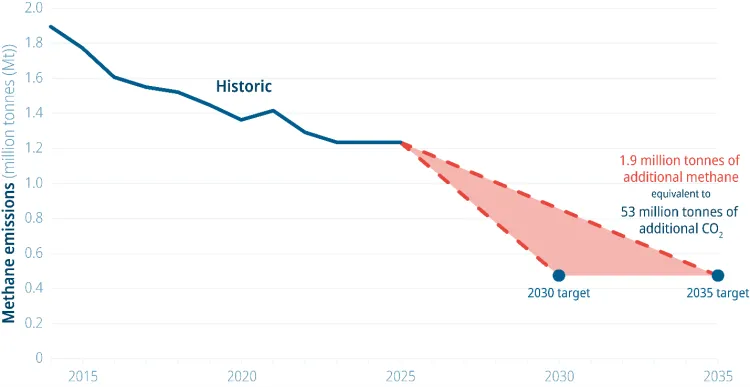

It's the same with methane emissions. Every day the province delays deeper reductions, it sends more methane into the atmosphere, and those emissions add up. According to our analysis, delaying Alberta’s implementation of the 75% target by five years would cumulatively result in 1.9 million tonnes of additional methane in the atmosphere. That’s the equivalent of over 53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (using a 100-year timeframe).

To put that into context, this methane delay will result in about the same amount of emissions as is produced by 12 million gasoline cars over the course of a year. Or, roughly half the cars registered across Canada.

In other words, to make up for the impact of delaying this target, one thing we could do is take about half the cars off the roads in Canada for an entire year. This is a far-fetched scenario, but it is reflective of how much harder the rest of the economy has to work to reduce emissions when the oil and gas sector is let off the hook.

Figure 1. 75% reduction in Alberta’s oil and gas methane emissions (from 2014 levels) by 2030 versus 2035

Data source: Government of Canada, National Inventory Report 1990–2023: Greenhouse gas sources and sinks in Canada (2025)

Faster makes us stronger

Okay, but Alberta committing to a 75% target – even if it happens later - is still a pretty big win, right? This is what the federal government has essentially argued when asked in media appearances over the last week.

But when we think about how far behind Alberta already is on methane policy, that logic doesn’t hold up.

Alberta had already been mulling a reduction target of 75-80% by 2030 (from 2014 levels) - first mentioned in its 2023 Emissions Reduction and Energy Development plan. But the province dragged its feet and has now fallen clearly behind leading jurisdictions in regulating oil and gas methane emissions.

For example, while other jurisdictions have prohibited routine flaring, the Alberta Energy Regulator failed to enforce its own solution gas flaring limit, before simply removing the limit altogether. Despite knowing that methane emissions are underestimated and underreported, to our knowledge Alberta has not yet integrated measurement data into its methane model to improve accuracy and ensure progress is tracked credibly. Alberta is also the only producing province not to have introduced a timeline to phase out emitting pneumatics (natural gas-powered devices that serve functions like opening and closing valves). Holding Alberta to the 2030 target was an opportunity to ensure the province meets a minimum standard.

Now the foot-dragging can continue – and there’s no excuse for it. Since methane is an extremely potent gas, the sooner we quit emitting it, the sooner we mitigate the worst near-term impacts of climate change. Deploying solutions to reduce methane emissions creates good jobs. Reducing methane emissions prepares us to diversify trading partners with jurisdictions that are seeking provably low-methane energy imports, like the European Union, Japan and South Korea. The time to differentiate Canadian gas is now, not later when we will be struggling to compete amidst a an oversupply of LNG. That’s why, in our view, there’s nothing more “climate competitive” than fast action on methane.

The MoU’s delay on methane was a misstep. Ottawa and Alberta will now negotiate an equivalency agreement on methane by April 1, 2026. Equivalency agreements are supposed to mean that a province designs its own regulations, which might have slightly different features, but nevertheless reach the same emissions outcomes as the federal regulations. It’s very hard to see how equivalency can now be possible when Alberta’s 2035 commitment is, in absolute terms, demonstrably weaker than the federal 2030 target. And, since there is not enough time between now and April for Alberta to develop regulations (much less conduct robust stakeholder engagement), it’s also not clear precisely what Alberta is going to present to Ottawa in these negotiations.

A step backwards for provincial cooperation

Finally, as with so many other aspects of the MoU, holding Alberta to a lower standard on methane is bound to make other provinces wonder why they’re not getting the same treatment. As our analysis has shown, British Columbia’s track record on methane has been very impressive – the province met its 2025 methane target early and was the first in Canada to legislate a 2030 target and regulations to get it there. What’s more, B.C.’s action is paying dividends – its industry reduced methane emissions while nevertheless growing production of oil and gas.

In other words, by lowering the bar for Alberta, the federal government has introduced a new layer of risk surrounding their claims that B.C. gas – more of which is set to be exported as LNG – is some of the “lowest-carbon” in the world. While Premier Eby has stated that he doesn’t think B.C. should be racing to the bottom with Alberta on methane, B.C. producers are likely to look at what’s just happened in Alberta and increase pressure on the B.C. government to relax its rules too – and B.C., understandably, may now find that pressure harder to withstand. In that way, the federal government just put at risk its own statements about the “climate competitiveness” of B.C.’s LNG industry, just so Alberta’s producers could get a five-year holiday from implementing the tried-and-tested technologies that would reduce their methane emissions. Was it worth it?