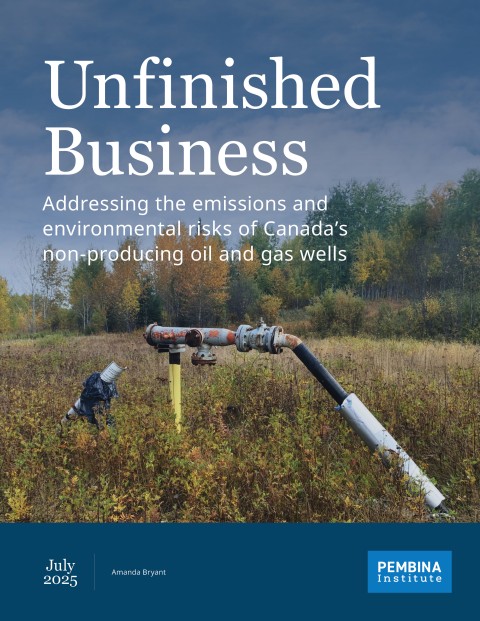

There are estimated to be over 520,000 non-producing (inactive, suspended, abandoned and orphaned) oil and gas wells in Canada. While many are located in relatively sparsely populated rural areas, they nevertheless can be found close to homes and buildings, and some also exist in urban population centres. There is broad consensus among government, regulators, industry and the public that wells that have reached their end-of-life should be properly plugged and reclaimed, to return the land to its original state and allow landowners and communities to reclaim the land for other uses. As such, there has been a growing public discussion over several years about appropriate policies to manage the closure of wells and to ensure that polluting industries (oil and gas companies) honour their obligation to shoulder the financial burden of this remediation work. These conversations are especially important as governments consider new policy options to tackle the issue of non-producing wells, such as Alberta’s proposed Mature Asset Strategy, which could end up placing the financial burden on taxpayers instead.

However, there has been comparatively less focus on the environmental risks and health hazards associated with these legacy oil and gas assets. These include their potential to leak methane and other pollutants into the atmosphere and into groundwater. Canada’s non-producing wells are estimated to have been responsible for around 11% of total methane emissions from Canada’s oil and gas systems in 2023 (230 kilotonnes of methane). Gaining a greater understanding of these risks is important if Canada’s governments and regulators are to design appropriate policy to address what is as much an issue of public and ecological health as it is of land-use planning and private sector asset management.

What is more, as the global energy transition accelerates and Canada’s oil and gas industry faces an increasingly competitive global market, it is reasonable to expect that shifting economics and aging infrastructure will cause faster growth in the population of non-producing wells in the years ahead.

Our report identifies key trends on methane emissions from non-producing wells and provides policy recommendations. To do this, we analyzed the two main sources of methane emissions data — industry reports to energy regulators and academic studies — and brought our findings together in this report.

Our analysis revealed the following:

- Tens of thousands of non-producing wells in western Canada are waiting to be plugged, remediated, and reclaimed.

- In Alberta and British Columbia, nearly half of suspended wells (those which in theory could be put back into production at any time) have been suspended for over 10 years.

- Leaks from non-producing wells are typically low but vary across regions and could contribute significantly to Canada’s emissions profile on a cumulative basis.

- Leaks that are designated as “serious” can remain unresolved for years or decades.

- Factors such as well type, history, status, construction, and plugging materials could help determine how likely a well is to leak, but official data on these attributes is often incomplete or inaccurate.

Based on these findings, we developed four main policy recommendations for non-producing wells:

- Disincentivize long-term well inactivity and improve leak databases through regulated closure timelines and quotas, strengthened testing and repair requirements, improved data collection and management, and enhanced enforcement.

- Improve measurement, monitoring, reporting, and verification by funding measurement and monitoring initiatives, strengthening reporting standards, and prioritizing data quality checks and data transparency.

- Tailor methane mitigation to the regional context by gathering region-specific data on well attributes and emissions, analyzing trends and identifying known problem wells, and using this information to design region-specific mitigation strategies.

- Characterize and mitigate risks of methane leaks by collecting regional data on risk factors, using a range of tools and strategies to identify problem wells, and prioritizing leak monitoring at potentially high-risk wells.

Note: This report was revised on August 7, 2025, as follows:

- Pages 1, 6, 20: Statement that emissions from non-producing wells account for 13% of unintentional emissions from Canada's oil and gas systems was revised to say that they account for 11% of the sector's total methane emissions.

- Page 6: Footnote 17 was added (resulting in numbering changes to the remaining footnotes).