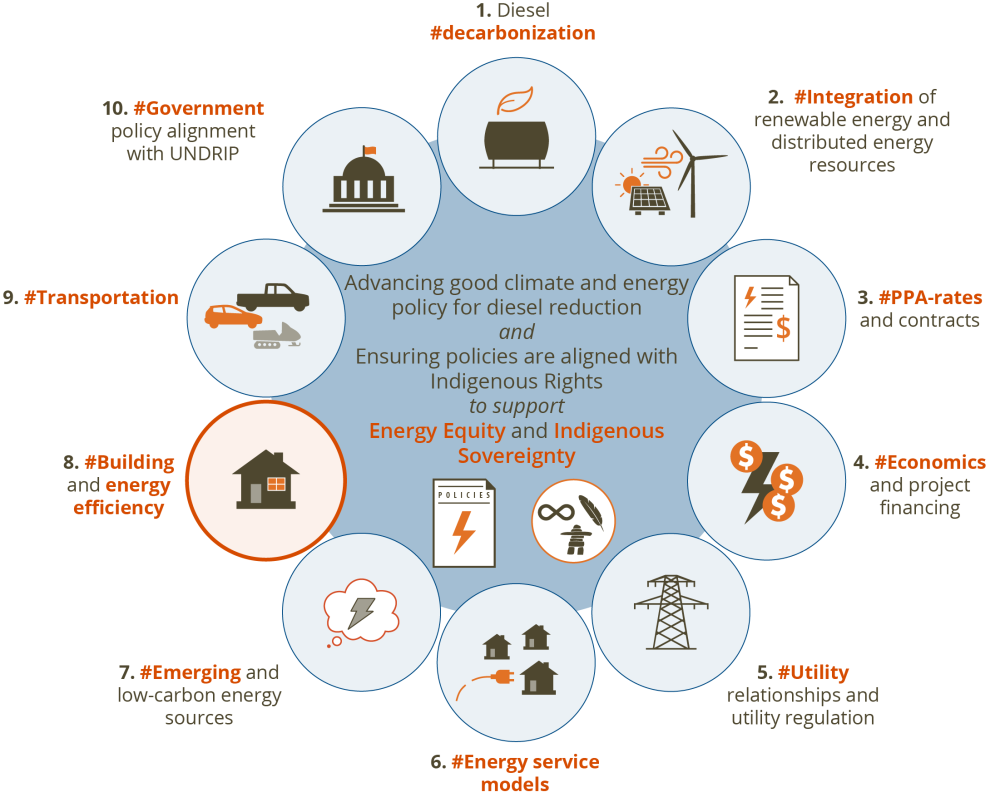

This is the ninth publication in Climate and energy policy advancements: Eliminating diesel in Canada’s remote communities, a series providing insights, details and analysis of each of the specific policies we advocate for under our Renewables in Remote Communities (RiRC) program and the Indigenous Off-diesel Initiative (IODI).

Addressing building inefficiency is increasingly a priority as communities and governments look to reduce diesel reliance. These improvements cannot be made without acknowledging and addressing that many of the issues with housing in these communities are a result of past and persisting government policy.

Homes are often mouldy and have insufficient heating and ventilation systems. Many communities are faced with chronic housing shortages, resulting in overcrowded homes and exacerbating already poor living conditions. These conditions contribute to communities facing higher rates of physical and mental health problems, which has a negative impact on the overall health levels within the community and impairs economic development.

In our report Diesel Reduction Progress in Remote Communities, we found that over half of the total diesel consumed in remote, often northern, communities is associated with heating buildings and homes. For federal and provincial governments to meet their commitments to support Indigenous communities to get off diesel, they must take a quality housing first approach.

To do this, governments should take the following actions:

- Develop community capacity to lead energy efficiency and building improvements

- Deep retrofit existing buildings so they are more energy efficient and offer better air quality

- Ensure new buildings and homes are low carbon and culturally appropriate

Significant financing is needed to address the existing infrastructure gap. In their Energy Foundations report, Indigenous Clean Energy estimates it will cost $5.4 billion by 2030 to retrofit Indigenous housing and meet demand for primarily rural, remote and on-reserve housing.

They also suggest that in the long-term, this initial investment for deep retrofits and housing improvements is estimated to have significant socio-economic benefits in those communities, including over 47,000 good full-time-equivalent jobs, $1 billion in household energy savings over 10 years and an $11 billion increase in home values. It also has the potential to significantly reduce diesel use in these communities.

Deep retrofit projects improve more than energy bills

Cost savings on energy bills for building owners is the most immediate benefit of retrofitting buildings. This is especially important for remote communities. Our report on diesel subsidies shows that energy bills in these communities are six to 10 times higher than in the rest of Canada. The cost of fuel used to heat buildings is dramatically increasing.

Reducing reliance on diesel through energy efficiency improvements and fuel-switching has the added benefit of reducing the likelihood of diesel spills that result in adverse health impacts on both people and the environment, and high costs for remediation and cleanup.

The benefits of building retrofits are not limited to cost savings and environmental improvements: infrastructure can be made more resilient; health and overall quality of life benefits can also be realized.

Housing and health in remote communities are directly linked. Remote communities experience higher rates of tuberculosis and other respiratory tract infections than any other group in Canada.

Studies conducted in Indigenous communities throughout Ontario and Nunavut show that the key to addressing these serious health issues is reducing overcrowding and improving indoor air quality. This can be done through constructing energy efficient, low carbon, well-ventilated, culturally appropriate buildings and implementing health-centered measures in existing buildings. This includes improving insulation and air sealing in building envelopes, fuel-switching heating systems and upgrading ventilation to decrease indoor air pollutants and pathogens and address persistent problems such as mould and insufficient heating.

The need for major building repairs due to insufficient and deteriorating building infrastructure in remote communities is only going to be amplified as communities face increasingly extreme weather conditions as a result of climate change. The impact of which is already being felt by some communities including Tuktoyaktuk, NWT, where permafrost melt and rapid erosion threaten several community buildings due to building foundation subsidence and shoreline loss. Future requirements for air conditioning can also be expected as a result of warmer summers – fuel-switching with heat pumps will pre-empt these cooling needs.

Updating energy efficiency standards and construction and renovation practices tailored to the climate conditions of remote, often northern, communities and centered around resilience and health will help mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Funding and policies need to recognize the unique constraints of remote communities

To date, government has neither prioritized nor provided adequate funding to support the massive effort needed to improve building efficiency and safe living conditions in Indigenous communities.

Natan Obed, President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami estimates that “the cost of ending the [Inuit] Nunangat housing crisis is almost 10 times more than what the federal government is currently providing to Inuit.”

But it is more than just funding; poor policy design, inadequate support for program implementation, and a lack of focus on community and Indigenous government-driven initiatives is also a significant barrier to creating adequate housing in these communities.

Government policies and programs should be simple and accessible to applicants to increase their uptake. Restrictive application requirements, including income requirements and limited access to residents with outstanding bills, have led to less than half of repair applications to the Northwest Territories Housing Corporation being fulfilled, according to the Corporation’s 2020-21 Annual Report.

The Corporation also cites a lack of funding and limited internal capacity as primary reasons for the territory’s repair demand being unmet. This has caused housing affordability, suitability and quality to continue to deteriorate. A 2019 survey from the NWT Bureau of Statistics found that approximately 43 per cent of dwellings in the territory had one or more issues that needed to be addressed.

Place-based solutions

Addressing the chronic funding gap for housing and energy efficiency improvements cannot be delivered through existing program models as they put too many stipulations on who controls the funding and where it goes, hampering uptake. New funding streams must respond to the longstanding requests of many Indigenous governments that “Indigenous peoples… are best placed to address the housing needs and priorities of their people and communities.”

The Federal Government’s recent “first-of-its-kind investment” of $78.6 million to the Tłı̨chǫ Government, Gwich’in Tribal Council and Délı̨nę Got’ı̨nę Government for housing and infrastructure projects is an example of the funding model that should be adopted elsewhere. It allows communities to allocate funding to immediate housing needs and ensure community members fully benefit through local training opportunities.

But so much more of this type of funding is needed, in addition to better policies and programs that also directly engage and involve local communities in the solution. As Ken Kyikavichik, grand chief of the Gwich'in Tribal Council points out, this “is just a start for the very dire infrastructure gaps that our communities face."

Local initiatives have proven to be successful where provincial and territorial programs have fallen short. Haílzaqv Nation’s heat pump project is a prime example. The community has installed heat pumps in over a third of community homes; the goal is to have an additional 120 heat pumps installed by the end of summer 2022.

At the same time, government programs need to incorporate capacity building so that communities can continue to benefit from participating in building retrofit projects and maintain control over community assets and upkeep.

Examples of the capacity building programs necessary to facilitate building energy efficiency improvements include the CMHC’s Housing Internship for Indigenous Youth and the IESO’s Education and Capacity Building Program because they ensure the expertise and knowledge needed for these projects are established within communities. These programs are essential in ensuring that installation and ongoing maintenance needs are not outsourced and communities can continue to benefit economically from energy efficiency projects by finding local solutions through training and skill development programs. The Pembina Institute’s report on future skills identifies the many skills and roles needed to ensure Canada’s homes and buildings meet 2050 net zero emissions targets.

Additionally, programs designed to support deep retrofit measures must consider traditional building methods and culturally appropriate design, as per the Indigenous Homes Innovation Initiative. Relying on third parties who are not familiar with needs specific to the community becomes a logistical challenge, increases costs and is less likely to be as successful as community-led initiatives.

Beyond growing skills in trades, capacity building programs should target providing training for local residents to be designated as their community’s energy manager to provide oversight and coordination of building and energy needs and projects. This will ensure that retrofits are more accessible and communities can independently conduct continuous management and monitoring of project performance.

Funding must be flexible in both amount and timeframe to account for unexpected delays, contingencies and unexpected cost increases associated with more complex logistics required in reaching and working in remote communities. Having a local community representative overseeing these programs would ensure these issues are identified early and planned for.

Supporting implementation through better policy centred around Indigenous leadership

New policies and changes to existing policies should be co-developed with Indigenous peoples.

The potential for reducing diesel consumption through retrofits is significant. Just improving 20 per cent of the building stock in remote communities with a 30 per cent decrease in heating requirements could result in approximately 64 million litres annually of avoided diesel – a nine per cent reduction in total fossil fuel consumption in remote communities from 2020 levels. In comparison, diesel reduction projects undertaken from 2015 to 2020 only resulted in a 12.3 million litre reduction annually, a mere two per cent reduction in total fossil fuel consumption in remote communities from 2015 levels.

In addition to drawing from earmarked funds for energy projects, deep retrofit programs for remote Indigenous communities can also be established through healthcare and infrastructure budgets, such as those in the Investing in Canada Plan. Improvements to building quality directly improve the poor health implications of inadequate housing. Because of the cross-sectoral benefits of deep retrofits, funding should be streamlined to achieve mutual goals and maximize benefits.

With much of the infrastructure in remote communities needing significant repairs, there is an urgency to retrofit not only to get off diesel and drive down energy demand, but also to remove carbon emissions from our buildings, make them healthier and safer and improve the living conditions and cultural suitability of homes in remote communities.

Improving buildings in remote communities is long overdue – homes are unsuitable, overcrowded, inefficient and unhealthy. Addressing insufficient housing is essential to reducing diesel demand in remote communities while also addressing pressing health and climate challenges. Making strides through better government policy design and investing in growing local capacity and expertise around building infrastructure are first steps to signal that government is taking housing and the ramifications of poor housing seriously.

Next up: A dive into electrifying vehicles in remote communities.

Additional reading

- Indigenous Clean Energy: Energy Efficiency Funding Database

- The Effects of the Housing Shortage on Indigenous Peoples in Canada

- For Indigenous by Indigenous

Related publications

Net-Zero Skills

What will Canada need for the coming energy transition?

Climate and energy policy advancements: Eliminating diesel in Canada’s remote communities

Publications in this series:

- Rethinking energy policy in Canada’s remote communities

- How to boost renewable energy integration in remote communities

- What’s a fair and equitable price for renewable energy in remote communities?

- Better government policies will unlock the cash remote Indigenous communities need for clean energy

- Reducing emissions from diesel generators in remote communities

- When business-as-usual is a barrier to clean energy

- From diesel dependency to energy empowerment

- Three clean energy options that could help replace diesel

- Remote communities transitioning to clean energy need better housing

- How remote communities should be included in the push to electrify transportation

- Government action on UNDRIP and the clean energy transition