This is the final article in a three-part series based on the findings of the report Accelerating Market Transformation for High-Performance Building Enclosures. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

Subnational governments have a key role to play in accelerating the market transformation for high performance buildings. In Part 2, we discussed some policies adopted in Western Canada to encourage Passive House developments today and to shift the building code to a comparable level of performance by 2030. In Part 1, we showed how the demand for Passive House buildings and training has increased as a result of these policies and the leadership of practitioners.

Subnational governments have a key role to play in accelerating the market transformation for high performance buildings. In Part 2, we discussed some policies adopted in Western Canada to encourage Passive House developments today and to shift the building code to a comparable level of performance by 2030. In Part 1, we showed how the demand for Passive House buildings and training has increased as a result of these policies and the leadership of practitioners.

So if this transformation is underway, why do we need policy-makers to get involved? We are on a timeline, and must pick up the pace. Each building allowed to be built to current standards is a 50+ year liability in a world that needs to be almost fully decarbonized within the next 30 years. To prepare the industry to deliver Passive House levels of performance consistently in less than 15 years is a challenge that requires vision and planning.

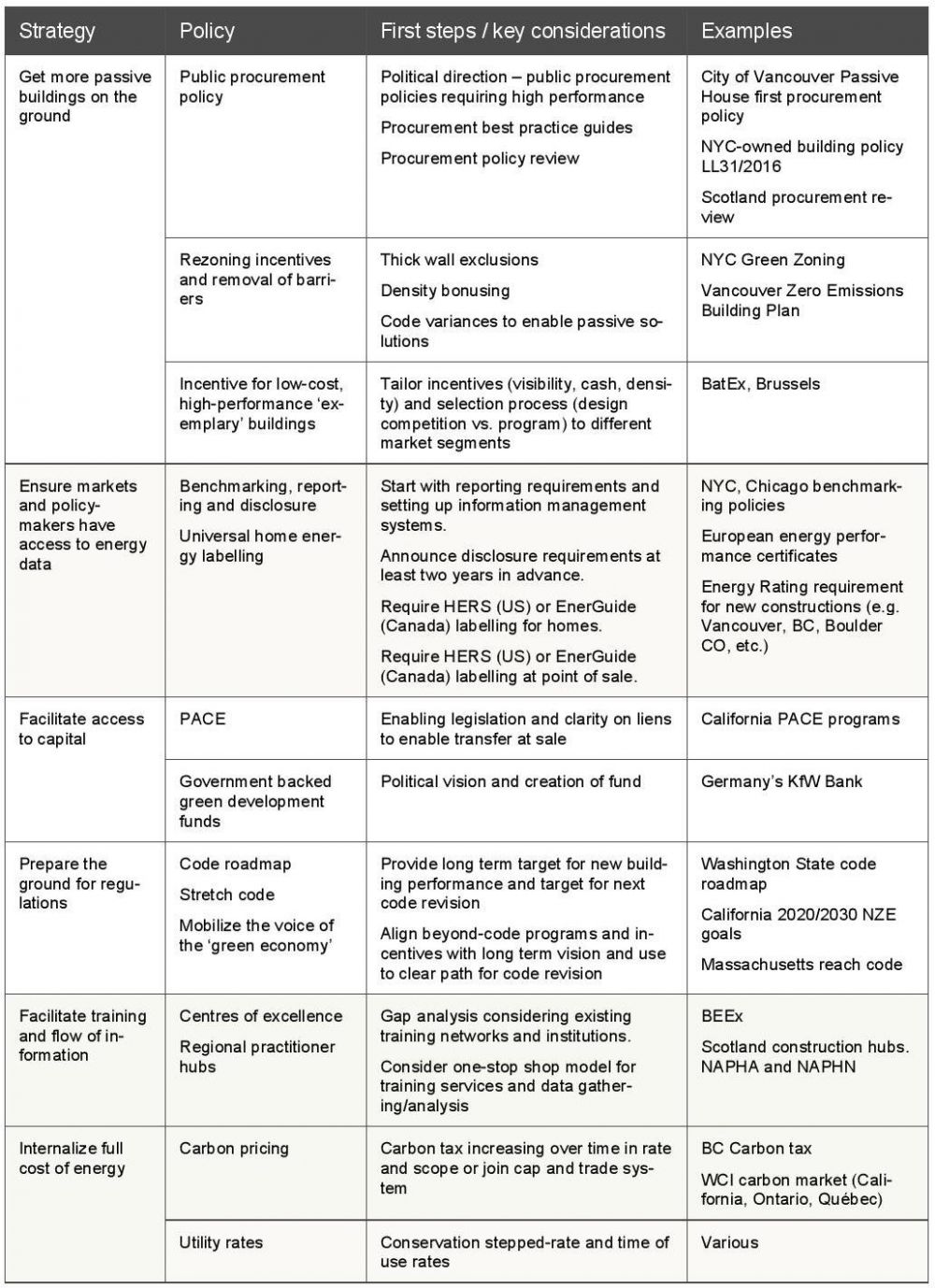

What would a comprehensive policy package look like? Based on our review of public policies in Europe and North America, local, state, and provincial governments efforts should focus on six strategies (Table 1):

- Get more passive buildings on the ground, today. It takes time for supply chains to stock the high performance components needed, and for professionals and trades to develop expertise to design and construct passive buildings. The sooner we start, the better: the best market transformation strategy is a shovel in the ground. To this end, subnational governments should design public procurement policies, rezoning policies, and incentives programs to target passive house levels of performance, rather than allocating points for ‘marginally above code’ performance. Prioritize projects that are affordable and replicable (particularly for the MURB sector) and those with high visibility to the public (e.g. city halls, libraries, schools, hotels). To maximize the learnings from these leading projects, provide incentives for developers and owners to share data on the project economics and design strategies and to collaborate with research institutions to monitor performance post-occupancy.

- Free up additional capital to cover incremental costs. Provinces and states can use government bonds to provide low-cost capital for loans and incentives for high performance new construction and refurbishments. If well designed, these public investments can be cost-neutral (or even cost-positive) for governments, because the economic activity they generate also lead to an increase public revenues through taxation. For example, Germany’s KfW development Bank returns to the public coffers four to five times the amount of public funds originally invested by the government. Alongside this public financing, private financing can be encouraged by mechanisms such as Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE), which decrease the risk of default by tying the loan to the property title.

- Ensure markets and decision-makers have access to energy information. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it: comparable and validated energy data must be made available to the market for the benefits of energy efficiency to be reflected in prices and assessed value. States and local governments should require benchmarking and reporting based on square footage, starting with larger buildings first and including smaller ones over time. They should also require home energy labelling for new construction and at point of sale/renovation. These will provide the feedback mechanisms needed to guide code evolution and facilitate valuation of energy efficiency and market positioning of high performance buildings.

- Prepare the ground for regulation. States and provinces should send clear regulatory signals to the market; defining mid- and long-term targets for energy code performance allows time for supply chains and training providers to prepare for these changes. It also provides an incentive for builders to skip the middle steps and learn directly how to build high-performance buildings, giving them an edge on the market and minimizing the investment needed to change practices at each code change. Code developers should use benchmarking data to monitor impact of energy code changes as we progress towards 2030 targets, and adjust accordingly through codes updates or bulletins.

- Create information sharing hubs for training, research, and outreach. High performance buildings are not rocket science, but there is a learning curve. Having set targets and a vision for where the industry is going, we must ensure that professionals, trades, contractors, owners, managers, building officials, and assessors are prepared for the next generation of energy codes and high performance buildings. Governments support the institutions and agencies that provide some of this education, research, and outreach so they can develop new curriculum and prepare to meet an increased demand as codes come into force. In addition, a central coordinating body should be created (or mobilized) to facilitate access to existing training resources, assess the readiness of the industry, and work with training providers and manufacturers to fill capacity and supply-chain gaps.

- Internalize the full cost of energy. Most economists agree that setting a price on undesired externalities and letting the market innovate to meet the new conditions is more cost effective than regulatory approaches. California, Québec, and Ontario’s cap and trade system and B.C.’s carbon tax provide successful examples of how subnational governments can set a price on carbon pollution. Unfortunately, current levels of carbon pricing are still much too low to drive construction and renovation decisions towards deep energy efficiency and decarbonization. Various businesses in the building sector have called for increased carbon pricing, for example in CERES’ Building and Real Estate Climate Declaration in the U.S. and the Call for Action on Climate and Energy in the Building Sector in Canada. Reallocation of energy subsidies and utility rate design are other tools state and provincial governments can use to correct the failure of our energy markets to minimize waste and pollution.

A market transformation has started, and uptake is accelerating. Hopefully, in a decade or so, we will be comfortably seated in our new (or renovated!) Passive House office or home, and look back in awe upon the days when we accepted buildings to be drafty, stuffy, and wasteful. Unfortunately, this future is uncertain: nothing guarantees that this budding market transformation will ripen to create a new normal. The barriers are significant: low energy prices, the absence of a meaningful price on carbon pollution, split incentives, and a long list of behavioral biases that often leads us to ignoring cost-effective efficiency projects (inattention, imperfect information, hyperbolic discounting, etc.). The creative minds of Passive House designers, builders, and contractors, and of high performance component manufacturers can solve any technical issues we will face along the way. But if we want this technology to go mainstream, and fast, we need government to address these market failures.

Subnational governments have been successful at implementing progressive building policies. Their leadership will continue to be pivotal in the evolution of low/no-carbon building policies given the current White House administration’s lack of interest.

Table 1. Strategic actions for market transformation

Tom-Pierre Frappé-Sénéclauze is a senior advisor with the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute, a non-profit think-tank that advocates for strong, effective policies to support Canada’s clean energy transition. He is the lead author of the report Accelerating Market Transformation for High-Performance Building Enclosures.

This article originally appeared on Insight, the blog of the Building Energy Exchange, ahead of the New York Passive House 2017 Conference & Expo.