Imagine you were considering getting a mortgage and your bank offered you a fixed interest rate at five per cent. You sign up, but when you go to make your first payment, the fine print states you are actually being charged 60 per cent interest. Would you feel cheated? Would you be able to handle a 12-fold spike in rates? And if you had realized the true cost, would you have signed those mortgage papers in the first place?

That's the situation facing a joint regulatory panel Alberta and Canada established to review the environmental impacts of the next massive 100,000 barrel-per-day oilsands mine, proposed by Shell north of Fort McMurray. According to an analysis commissioned by the Pembina Institute using government and industry data, the "too good to be true" environmental assessment submitted by Shell underestimates actual impacts by 12 times.

As the Canadian Press reported yesterday, this case shows there is a major disconnect between the government departments focused on economic development, and those focused on environmental protection.

Under Canadian law, large projects like oilsands mines must conduct a cumulative effects assessment (CEA) to determine what impacts the project will have on the environment, combined with other developments in the area. The assessment is also meant to inform decision making about whether, given those likely impacts, approving the project is in the public interest.

Oilsands boosters ranging from the Government of Alberta to the energy companies, as well as regulators like the National Energy Board, are ready sources of information about the huge numbers of oilsands projects jockeying to be built. But selective amnesia seems to set in when future development is presented for the purposes of assessing oilsands environmental impacts at hearings seeking to determine whether or not those projects should go ahead.

In the case of the Shell plan, for example, the company's assessment fails to take into account at least 11 planned oilsands projects, logging plans for forest companies that share the same landscape, mandatory exploration disturbance from over a million hectares of oilsands leases, and the impact of forest fires on a landscape that burns frequently.

That's why the Pembina Institute (as a member of the Oilsands Environmental Coalition, along with our partners Toxics Watch Society of Alberta and the Fort McMurray Environmental Association) submitted a report to the joint panel, revealing there are too many errors with the assessment that has been submitted by Shell to proceed to a hearing for the project.

Our submission shows that Shell low-balled the amount of known and proposed disturbance in the region by 12 times. So, rather than five per cent of the landscape being disturbed over the next 50 years, the actual figure is likely to be closer to 60 per cent. Because of this error, Shell's assumption that the project would lead to no significant environmental impacts is not valid.

Without taking into account additional impacts in the area from other mines, logging and forest fires, it is not possible for the joint review panel to make an informed public interest decision on whether the region can sustain the cumulative impact of proposed development.

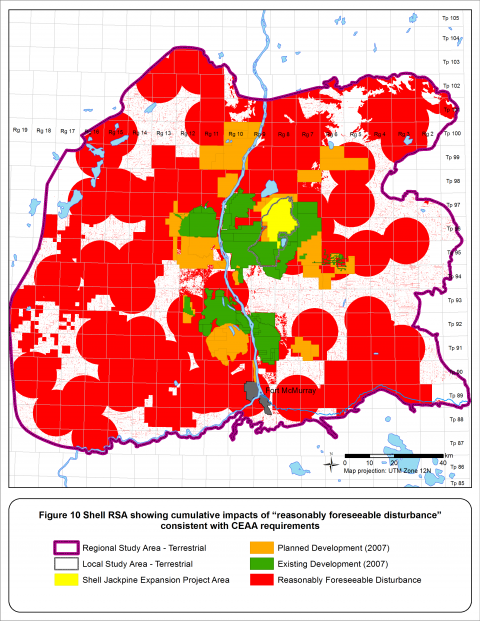

As the map below indicates, Shell made a number of serious errors, and the assessment that it submitted in 2007 is now out of date.

Above: Shell's "planned development case" (in orange and yellow) is a fraction of the reasonably foreseeable disturbance mapped by the Pembina Institute and the Oilsands Environmental Coalition. Source: Commissioned by the Pembina Institute, conducted by Global Forest Watch Canada.

The Governments of Alberta and Canada are mandated to ensure cumulative impacts are assessed appropriately. Alberta's regulator, the Energy and Resource Conservation Board (ERCB), states that: "Alberta relies on the best information and science available to predict the impacts and cumulative effects of a proposed industrial activity on the surrounding environment. This provides the foundation to decide whether the activity should proceed."

The assessment submitted by Shell certainly doesn't meet this standard — and that is why the company needs to go back to the drawing board and complete a proper assessment.

Our recommendation to oilsands proponents and regulators alike is this: tell the whole truth about anticipated future development.

Canadians have a right to know about the high environmental cost that accompanies oilsands expansions and the impacts of other land-uses in the region. Given the proposed pace of oilsands expansion, companies must provide decision makers and Canadians with a clear picture of the significant trade-offs that would be required to support such a rapid scale-up of production.