The federal government’s just-released 2012 update to Canada’s Emissions Trends is an important report from Environment Canada that explores the trends expected to shape Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions this decade. The release of the first edition last July, along with this week’s updated version, are welcome because emissions projections like these are crucial to assessing the impact of Canada’s policies against the commitments the government has made to Canadians and to the world.

The spin from the federal government on this year’s report was that Canada is making "significant progress" towards its emissions targets, and this progress is the "result" of federal climate policies. While there is some good news in the report, this sort of messaging does little to help Canadians have a serious conversation about climate change and what Canada is going to do about it.

Instead, in releasing this update, the federal government is overstating its own efforts to tackle greenhouse gas pollution and understating the challenge facing federal and provincial governments in reaching our climate commitments.

The back story on Canada’s climate commitments

To understand the gap between where we’re headed and where the government wants to go, let’s start with the latter: Canada’s climate commitments.

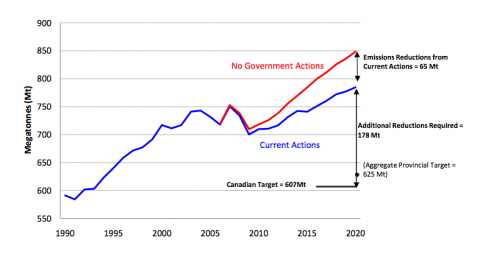

While the gap between our climate intentions and actions now appears somewhat smaller, the challenge of closing it has not shrunk an inch. Following the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Canada pledged to reduce its emissions to 17 per cent below the 2005 level by 2020. The federal government has reiterated this commitment many times since in the international negotiations and at home. (To its credit, the government continues to express this goal as reducing emissions to 607 megatonnes (Mt), despite a recent revision of 2005 emissions that would make the target slightly less stringent.) This is the flat black line in the bottom right of Figure 1 below, which illustrates the government’s target.

The blue line in Figure 1 illustrates where Canada’s emissions actually were headed, as of the 2011 edition of Canada’s Emissions Trends based on implemented federal and provincial policies. The blue line projections are measured against a reference case (the red line) in which emissions grow rapidly without any government climate policies, rising to 850 Mt by 2020. The difference between the red and the blue lines in 2020 was 65 Mt, which would get Canada only a quarter of the way to the 607 Mt we had committed to achieving in 2020. It’s a lot like a CEO promising investors she will cut costs by one million dollars but telling them she had only figured out a quarter of the plan to deliver.

Figure 1: Canada’s Emissions Trends, as projected in 2011

How 25 per cent turned into "half way there"

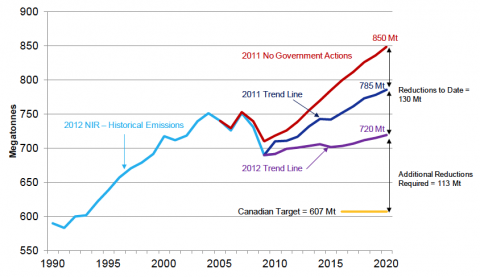

The 2012 edition of Canada’s Emissions Trends shows this gap has shrunk significantly in percentage terms. Rather than being a quarter of the way to our target (the blue line in Figure 2 below), we are now nearly half way (the purple line). Our CEO is delighted, but our investors might not see it the same way.

Figure 2: Canada’s Emissions Trends, as projected in 2012

It’s certainly tempting to give ourselves a pat on the back and conclude we must be much cleverer than we thought because we seem well on our way to having this climate thing licked.

But to understand what this means for meeting our commitments, we must look at what really accounts for this change. Why is this year’s emissions projection 65 Mt lower than last year’s? Has our CEO really beefed up her cost cutting plan, or are there other forces at work?

There are three key factors that explain why this year’s numbers appear to get us so much closer to our climate goal, compared to last year. Unfortunately, none of them has much to do with new action from the federal government.

- New accounting rules for forestry and land-use change: The government has projected that new accounting rules agreed to at last year's UN climate talks in Durban, South Africa, will allow it to count a reduction of 25 Mt from expected changes in forest management. This is now included in its projection and accounts for more than a third of the difference between last year’s and this year’s number. (In the CEO’s case, this might be similar to a change in accounting rules that let the company take some liabilities off its books.)

- A lower starting point: Actual emissions were 18 Mt lower than anticipated in 2010, meaning that this year’s projection begins at a lower point than last year’s. (In other words, costs turned out to be lower than expected in the first year our CEO’s plan to cut a million dollars, so the same plan that took her a quarter of the way before now goes a little farther, without any new effort.)

- Changes in Canada’s economy: The emissions intensity — the amount of greenhouse gas pollution per unit of economic growth — of the Canadian economy is dropping more quickly than expected. This is partly a consequence of changes wrought by the recession (heavy industry is recovering more slowly than anticipated, while our economy continues to shift away from traditional industrial sectors that produce a lot of emissions, toward more service-based industries with a lighter footprint), and partly due to consumers and industry making greener choices. For our CEO, the nature of her sector is changing to favour lower-cost activities, and her consumers are increasingly choosing products that cost less to produce. While both help to cut expenses, neither are evidence of her plan in action.

It’s encouraging to see efficiency improvements making their way into the numbers as Canadians choose more efficient vehicles, industry upgrades its equipment, and both work to cut energy waste in buildings. While federal policy has some role here, it is the leadership from the provinces that is really driving this change, with Ontario’s coal phase-out and B.C.’s carbon tax among the top examples.

Taking the credit without doing the work

While it’s important to understand the factors behind this year’s projections, it’s just as important to understand what has not contributed much to shrinking the gap.

There are three key factors that explain why this year’s numbers appear to get us so much closer to our climate goal, compared to last year. Unfortunately, none of them has much to do with new action from the federal government.The reduction expected from federal efforts is not likely to have changed much since last year’s report. The only new policies included here are regulations for heavy trucks (currently in their draft phase and projected to reduce emissions by three Mt in 2020) and passenger vehicle regulations for 2017–2025, which have not yet been drafted. In other words, the CEO’s cost cutting plan has hardly changed at all.

So where does all this new information leave us? Is it time to roll out the “mission accomplished” banner and sign the bonus cheques? Unfortunately, not quite yet.

While the gap between our climate intentions and actions now appears somewhat smaller, the challenge of closing it has not shrunk an inch. Canada remains wildly off course for meeting its target and the federal government still has not shown how it will address this.

As recent reviews by both the Environment Commissioner and National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy have found, closing the gap will require an urgent and substantial increase in federal climate action. The government’s plodding sector-by-sector approach simply will not deliver the necessary cuts to emissions within the time frame required. By the Roundtable’s estimate, meeting the target will require taking advantage of any and all opportunities to reduce emissions, up to a cost of $150 per tonne of emissions, by 2020. For context, BC’s carbon tax is currently set at $30 per tonne, Alberta charges $15 per tonne for the portion of greenhouse gas pollution companies produce above their targets, and the yet-to-be-finalized federal coal regulations are expected to imply an emissions reduction cost of $25 per tonne or less.

While the latest emissions trends numbers make it easier for those embarrassed at our quarter-of-the-way status to deflect criticism, they offer little indication that the government is prepared to meet its climate commitments. If our CEO has a plan to close the gap and deliver the million-dollar cost-saving solution, now would be a good time to disclose it.