Presto machine at Bathurst Station. Photo: Kelly O'Connor, Pembina Institute

The problem-ridden rollout of PRESTO cards in the City of Toronto hasn’t exactly gotten riders excited about the future of fare collection. It’s too bad, because this technology is more than just a sleek replacement for tokens. Fare cards lay the groundwork for all kinds of possibilities for improving our transit system. Among those possibilities is regional fare integration.

Establishing a uniform set of rules for pricing transit across the GTHA has been a provincial priority since the creation of Metrolinx. Some important concerns around fare integration include the impact on municipal autonomy in setting fares, the difficulty of implementation, and the potential impact on low-income riders. Fare integration is a conversation we need to have, and it is critical municipalities and the province get it right. It’s likely that we’ll see this file move forward this year, since SmartTrack/RER – a priority transit project for the City of Toronto – depends on revised transfer policies between GO and TTC. In fact, a new proposed concept will be discussed at the Metrolinx Board meeting tomorrow.

The current state of fares

Currently, the GTHA is made up of 11 transit agencies that set and manage their own fares. Riders can travel between most 905 municipalities for one fare, and a reduced co-fare is offered for transfers between GO Transit and 905 municipal systems. However, there is no fare agreement between the TTC and surrounding municipalities, nor with GO Transit, meaning that riders crossing the City of Toronto boundary are required to pay a double fare. This less than ideal system discourages transit use and adds to our existing congestion problem, as more people are driving part – if not all – of their commute to avoid the double fare.

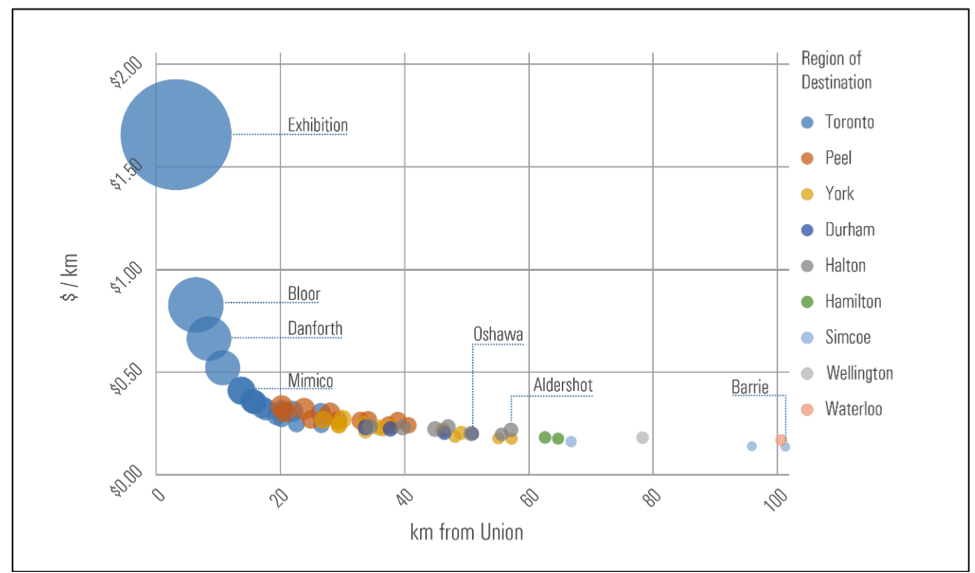

There are other inconsistencies in the current system. For example, although GO transit uses a base fare plus a distance component, a trip on the GO costs less on a per-kilometre basis for long trips as compared to short trips. This deters riders from using GO for short trips.

Big potential

If done right, a uniform pricing structure across the GTHA could bring major benefits in terms of equity, ridership and city-building. We think there are at least five reasons to get excited about fare integration.

1. Increasing ridership without building anything new

Imagine you live in Mississauga and work in the west part of Toronto. Your morning commute might only be a few kilometres, but to take transit, you’d have to pay fares with Mississauga Transit and the TTC, making your one-way trip cost upwards of $7.

For many people, cost is not the most important factor in the decision to ride – frequency and speed usually top the list – but cost still ranks high, particularly for low-income riders, who depend more on transit for access to destinations in their community.

Resolving the unfair price discrepancies would unlock new ridership without any additional infrastructure investment. A fare concept evaluation commissioned by Metrolinx in June 2016 found that addressing cross-boundary fares between Toronto and its neighbours can result in 26,000 more daily riders compared to the status quo in 2031.

2. Integrating services across boundaries

Under the current system, many transit routes end at municipal borders, meaning that riders have to transfer to continue their journey. In a regionally integrated system, it would be easier to match routes with the ways that people travel across the region, creating a more convenient service for riders.

3. Discouraging sprawl

The price of transit shapes urban growth. For example, by charging less per kilometre for longer trips, the current GO fare structure encourages commuting from greater distances. While we’re all in favour of incentivizing commuting by transit, this system of charging less per kilometre may also be incenting more people to choose to live in outlying areas, creating more sprawl. Conversely, a stronger distance-based component in fares could work along with land use policies to encourage more compact, transit-oriented development

4. Supporting Neighbourhood Improvement Areas

Toronto’s low-income areas are generally less served by rapid transit. Only 5 of Toronto’s 31 Neighbourhood Improvement Areas (NIAs) are served by TTC’s rapid transit network, but 15 NIAs are within 500m of a GO stations. Tying fares more closely to distance could improve access to GO transit for these populations, while also unlocking GO services for short trips within 905 municipalities. This will be especially important as GO moves toward all-day, two-way service.

5. Driving down car trips

Fare integration can make transit a more attractive choice for many who currently use a car for part or all of their daily trips. Metrolinx’s fare concept evaluation found that addressing cross-boundary fares between Toronto and its neighbours could eliminate 246 million vehicle kilometres travelled, while reducing car trips across the Toronto boundary to TTC park and ride lots by 20-25%. With an integrated fare, a certain number of riders would leave their car at home and instead take the bus to the subway – without paying twice.

Eliminating unnecessary car trips brings incredible benefits in terms of health and cost savings to individuals and to communities.

What’s the catch?

An integrated regional fare structure could take on many forms. Currently, Metrolinx is studying four concepts: modified status quo, zone-based, hybrid, and distance-based (the latter added this week). While each of these models has the potential to bring about the benefits described above, it’s nearly impossible to judge the merits before specific details (such as price) are proposed. Each concept comes with certain trade-offs, and may mean a big adjustment for riders and transit agencies in terms of fare collection practices.

To date, Metrolinx has indicated that a fare integration strategy should be revenue-neutral: for example, reducing double fares in one part of the system would be counter-balanced by relative increases in another part of the system. However, studies have demonstrated that a revenue-neutral arrangement won't lead to net ridership gains in the short term, which we believe should be the primary goal. As such, we encourage decision makers to consider an initial subsidy in support of fare integration as an investment in the transit system for the long term.

We suggest that this is a reasonable and modest investment to make, compared to the cost of building new infrastructure. Fare integration can bring immediate benefits for thousands of current and future riders, but to make it a reality, the conversations and negotiations will require give and take from all actors.

For more thinking on regional fare integration, see our submission to the Metrolinx Regional Transportation Plan Review.

Lindsay was the managing director for transportation and urban solutions for the Pembina Institute until 2019.